Oral and linguistic expressions

The storytelling song in Cesacastina

Narrative songs

“Oh sailor boy off to the sea, I’m going to sea on a breezeless day, to find my true love who has gone away”. Thus, begins a narrative song which is performed in both a powerful and a delicate way, handed down by the women of Cesacastina and well-known in the mountains and hills over a wide area of the Apennines. It tells the story of the ill-fated love between a young woman and a sailor who falls madly in love with her and marries her, after promising her father that he will be absolutely faithful and will respect his vows; the girl follows him onto the high seas where she drowns, shattering their dream of a life together. It is an enigmatic, painful text and each verse concludes in polyphonic form, with the voices that diverge leaving in the listener a feeling of suspension and identification with the sung story.

“In the morning, just like you pick up a pen and go to study, we picked up our pitchforks and went to dig the land. Then we had breakfast, then at midday our parents came and brought us food, we ate, then we spent that hour’s break singing, dancing, quarrelling, laughing and the days passed by”.

Emilia Ridolfi, November 26, 2012

The narrative song is a definition that identifies a typology of repertoires attested throughout the European continent, particularly widespread in northern Italy, with extensions in central Italy and a rarer presence in the south and in the islands. The narrative song, of which traces can be found as far back as the Middle Ages, emerged above all in the 16th century and is subsequently documented in vast areas of the Italian territory from the 19th century onwards.

The performance of narrative songs can be monodic or polyphonic, with or without instrumental accompaniment. The story contained in them is generally based on the complete development of a tale, concatenating strophes that construct a story about love and passion, often dealing with crime and cruelty, generally defined by few protagonists and a quick and concise sequence of facts and actions. For this reason, the narrative song provides for the immediate recognition of the verbal part and the prevalent use of Italian, although there are not infrequent dialectal additions and influences.

When polyphony dominates the song, the singers have fun performing chords, spacing , divarications and unisons before returning to the initial harmonic structure. Performed and transmitted in contexts of public or private entertainment, of an almost always collective nature, the narrative songs were sometimes the expression of particular specializations or, in the case of the singing story-tellers, of itinerant professionalism. Many popular songs in the Laga mountains were transmitted by the so-called camplesi (people from Campli’s nearbies), door-to-door storyteller singers who travelled around the territory periodically, encouraging the transmigration of the repertoires.

Don Nicola Jobbi first recorded a group of women from Cesacastina singing some narrative songs while they were working in the kitchens of the village school during a summer camp in 1965. Elgisa Giustiniani, Emilia Ridolfi, Maddalena Baldassarre and Costanza Romani sang a significant portion of their narrative repertoire, from La montanara ( The mountain girl) to La pastorella, (The Shepherdess) from Lu marënarë (The sailor) to Mia cara Emma (My dear Emma), a variant of La Madre Resuscitata (The reborn mother) collected by Costantino Nigra among the popular songs of Piedmont. In a subsequent visit to the village he also documented the elderly transhumant shepherd Palmerino Marrocco, holder of a vast repertoire of songs and poems in ottava rima , poetic fragments taken from the chivalric epics, lamentations and sacred cantatas for religious services, generally used during processions.

Cesacastina di Crognaleto (TE), Summer 1965.Recording by. Don Nicola Jobbi Study Centre Archive /Bambun.

Listen to the track

Narrative songs

Maddalena Baldassarre

Baldassarre Archive,

Cesacastina di Crognaleto (TE), May 1971.

Narrative songs

Portrait of Palmerino Marrocco

Photo by E. Chiapponi,

Albano Laziale (RM), 1920s,

Archive of Francesca Marrocco.

Narrative songs

Patronal festival

Romani family Archive,

Cesacastina di Crognaleto (TE), early 1960s.

Narrative songs

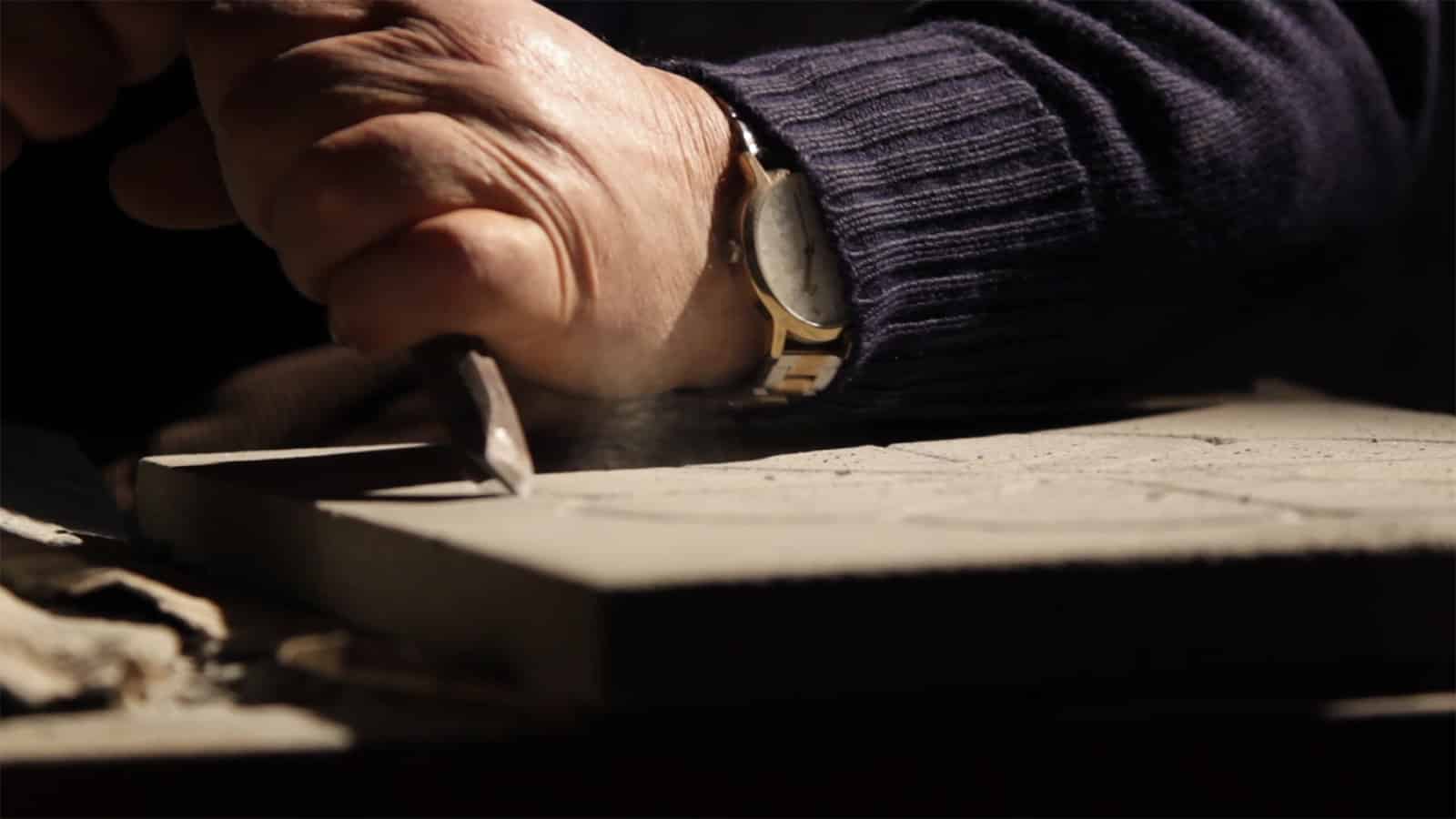

Emilia’s song

Photo by Gianfranco Spitilli,

Cesacastina di Crognaleto (TE), November 26, 2012,

Don Nicola Jobbi Study Centre Archive/Bambun.

Narrative songs

Costanza Romani

Romani family archives,

Cesacastina di Crognaleto (TE), 1970s.

Watch the video

My dear Emma

Cesacastina di Crognaleto (TE), November 26, 2012.Filming by Gianfranco Spitilli, Don Nicola Jobbi Study Centre Archive/Bambun

Cultural transmission and protection

In Cesacastina, as in the whole area of the Gran Sasso and Monti della Laga, the practice of narrative singing and, more generally, of the oral tradition of singing, appears to be strongly disrupted due to depopulation and the progressive loss of both the older generations and the occasions when the songs used to be sung: the evening gatherings in front of the fireplace or in the stables, some moments linked to outdoor work, especially during the rest periods, meetings in the tavern, domestic activities such as those encountered by Don Nicola Jobbi when he first recorded some narrative songs in the village in 1965.

These precious documents have contributed to spreading awareness of the songs and in some way facilitating their transmission even today, when direct intergenerational learning, within the community of Cesacastina, seems to have stopped.

Some recordings from 1965 were later published in Teramano, the third volume of the Documenti dell’Abruzzo, dedicated to the Alto Vomano and Monti della Laga in 1991 and, more recently, in online fact sheets with audio files, on the initiative of the Archivio Sonoro Abruzzo (Abruzzo Sound Archive) project (http://www.archiviosonoro.org/archivio-sonoro/archivio-sonoro-abruzzo/fondo-jobbi/cesacastina.html); moreover, a complete publication of them is planned by Gianfranco Spitilli and the Don Nicola Jobbi Study Centre. In fact, in recent years digital copies have been made and restorations of the original materials have been carried out,with the aim of allowing free consultation and publishing within the Jobbi Fund’s project for study, recovery and dissemination, run by the Bambun Cultural Association and the Jobbi Study Centre with the help of numerous national and international territorial and scientific institutions and the support of the Réseau Tramontana European project.